I mentored parents for many years. I enjoyed this work, the friendships I made, and the changes I saw in families. In the early days, I worked with families that were homeschooling. Later, I added parents who educated their children in private and public schools. One of the issues for all parents was how to help children/youth want to learn, enjoy the process, and take responsibility for their learning. No one system insulates parents from this dilemma. I began writing a series of articles titled The Education Adventure. These articles contained real experiences, from real families. Their stories are helpful when working to help children take on the adventure of education.

I mentored parents for many years. I enjoyed this work, the friendships I made, and the changes I saw in families. In the early days, I worked with families that were homeschooling. Later, I added parents who educated their children in private and public schools. One of the issues for all parents was how to help children/youth want to learn, enjoy the process, and take responsibility for their learning. No one system insulates parents from this dilemma. I began writing a series of articles titled The Education Adventure. These articles contained real experiences, from real families. Their stories are helpful when working to help children take on the adventure of education.

Important Questions

These are two questions that often surfaced while mentoring. The answers vary widely from family to family and from child to child. Observing how other families manage can assist in answering these questions for your family.

• How do you help them want to learn?

• How can you help children/youth take responsibility for their learning?

An Example from a Real Family

I had the privilege of working with a family who had an 11-year-old boy. Let’s call him Mike. They homeschooled. But as many of us do, even when our kids are in public or private school, mom pushed him. She wanted him to succeed. She wanted him to be proud of himself. Every day there was a lot of math, reading, spelling, science, etc.

This doesn’t sound much different from the mom who is using a private or public school, does it? At the end of the day, we feel responsible for how our children are doing in their schoolwork. It often feels as if the quality of their work shines a reflection on us, as parents. Are we helping them enough? Are we making sure they’re getting their homework done? Are they enjoying the education process? Do we feel overwhelmed with their school stuff and all the other things we manage?

Back To The 11-Year-Old

Mike had become somewhat belligerent about schoolwork, especially math. When his mom reached out to me, she didn’t think her son liked school. I was able to share information on how to make it feel more enjoyable and gave her some tools. They were helpful to her children, but we really made significant progress when I met with her son.

When I asked Mike how he was feeling about school, he said he liked it. He liked doing things as a family. He enjoyed reading together and alone. This surprised his mom. I asked him how he felt about math. He said he loved it; it was one of his favorite things. This also surprised his mom. Then I asked a pointed question, “Then why do you fuss about doing your math?” He responded that sometimes he wanted to read instead. I had to laugh. Doesn’t that sound like all of us? Sometimes you have things you need to do, but you want to do something else, and it makes you feel grouchy. It’s one of the reasons my daughter, Jodie, lets her kids take an occasional ‘sick’ day. : )

Since math had been the big issue between him and his mom, I asked him why he loved math. He replied that he liked working things out and solving problems. I said, “Then you would probably like architecture. It uses math to solve problems and work stuff out.” He said he loved architecture. This was something his mom hadn’t known. She had never talked with him about his math, except to ask if his assignments were finished. That week, she got books on architecture from the library and set them out. One day, they spent time together looking at pictures of famous buildings and talking about them.

Here’s another hard place many parents find themselves, as Mike’s mother had. We know what needs to be done, but we aren’t watching our children to see what interests them. We aren’t engaging in conversation. We’re not listening. We’re busy with life, and we want them to get their schoolwork done and do it well. However, when we ask questions and respond to what interests our kids, we help them connect schoolwork to their goals and dreams.

Mike’s mom and dad attended a seminar I spoke at a few weeks after we began working together. We had a conversation about their son and his math. Just that day, he had gotten mad at his mom over the math homework. He didn’t want to attend their family devotional or participate in family reading. He accused his mom of making him get behind in math because of all this other, unimportant family stuff.

I listened as the parents talked about the situation, and then I asked, “Why are you taking responsibility for Mike’s math?” His parents weren’t sure how to respond. I mean, don’t all parents manage their kids’ education and make sure they do the work?

At our interview, I asked Mike how he felt about overseeing his education, about being responsible for whether he learned math. He said he liked being able to choose what to study every day, but worried about being in charge. He said, “Sometimes I like having someone tell me what to do. It’s scary feeling I’m in charge.” Here he was fussing when his mom told him what to do, but he was intimidated by managing himself. This is the lesson everyone must learn, at some point, to live successful lives. It’s wise for kids to practice being responsible before starting high school, leaving home, or going to college. His mom saw that we can’t (and shouldn’t) do it all for our kids. They must learn to take responsibility. I’m watching this unfold in my own home this year with one of my teenage grandsons. Accepting responsibility is not always easy.

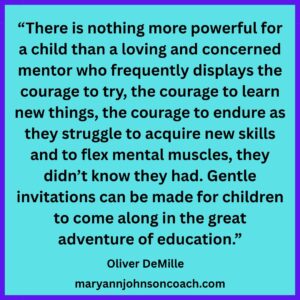

Let me share a powerful quote from an old friend, Oliver DeMille. “Freedom is the powerful, essential ingredient required for the development of courage. Students may become comfortable with being told what to learn and when to learn it. They may feel some fear or insecurity when offered the opportunity to choose. They may require time to engage in study of their own choosing. There is nothing more powerful for a child…than a loving and concerned mentor who frequently displays the courage to try, the courage to learn new things, the courage to endure as they struggle to acquire new skills and to flex mental muscles they didn’t know they had. Gentle invitations can be made for children to come along in the great adventure of education.”

I’ve written about the importance of parents continuing their own education (this can be in community classes, higher education, or good old-fashioned reading) because it builds confidence; confidence that the parent can learn and be an example to their family. It builds confidence in the child that they can learn by following the example their parents are setting for them. Parents need to model the behavior they want to see in their children.

I’ve also written articles on the value of seeing children’s sparks, what they are truly interested in, and how responding to those sparks can ignite a love of learning, which carries over into subjects they aren’t as passionate about. This is successful in all types of educational systems.

Ask Questions, Listen, & See the Spark

It’s hard to see sparks if we aren’t talking with and listening to our children. Mike loved math, but the only conversation he had with his parents about it was whether he had finished the worksheets. Think of all the wonderful ways this spark could be used to spur his desire to learn math on his own, to take responsibility for his education. His mom had followed up by getting books, and they were planning to visit an architect’s office to see what an architect does.

Sparks and your example are two things that can make a difference in your child’s personal education. You are the mentor for your children, regardless of where they attend school. It’s hard to convince your child that education matters if you’re not somehow engaged yourself. We can only invite our child to join us in the great adventure of education if we’re taking that adventure ourselves.

Remember what Dr. DeMille said, “There is nothing more powerful for a child than a loving and concerned mentor who frequently displays the courage to try, the courage to learn new things, the courage to endure as they struggle to acquire new skills and to flex mental muscles, they didn’t know they had. Gentle invitations can be made for children to come along in the great adventure of education.”

So, learn to tie fishhooks, learn cake decorating, take up Spanish, begin sewing, attend a community education class, or have a book in the bathroom that you read daily. Let your children see you learning. Talk to them about the challenges and joys, and they will begin to share their feelings with you. This makes for great dinner conversations. When you make this effort, it can ignite a love of learning and a desire to take responsibility. I’ve seen this work over and over again.