My mother had a stroke in February. She wasn’t doing well and was put in hospice. In the ensuing months, she had an astonishing recovery and will be leaving hospice at the end of December. Her current nurse, Laurie, said it’s a joy because it rarely happens.

Our hospice caregivers have been wonderful, and we’ve enjoyed getting to know them. They have made a difference in our lives. This week, we had a visit from Lynda Huddleston, who is the chaplain currently visiting us. She brought a story she had written to read to Mom. It shares a true event that happened at Christmas, when she was working in a care center.

I sat and wept as she read. It was a beautiful example of the gifts we give to others when our hearts have been touched. I asked Lynda if I could share it with you, my readers, and listeners. Thankfully, she said, “Yes.” These will be some of the best moments you spend as we wind down this Christmas season. ENJOY! Merry Christmas.

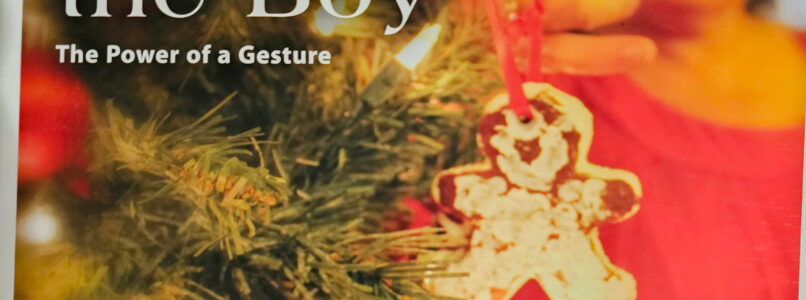

Peter and the Boy

Peter and the Boy

On the second Friday of the month, in the front room of our assisted living, you could always find music, laughter, and the soft rustle of anticipation—along with most of the ladies leaning in a little closer as Cowboy Andrew began to sing.

Tall beneath his Stetson, with a baritone smooth as molasses, he filled the room with country songs that stirred memories and sometimes tears. Andrew had been part of our calendar long before I joined the staff, and none of us imagined the day would come when he would need us. But when he chose our community for his father, Peter, to spend his last days, we were honored beyond words.

Peter arrived frail and worn from years of illness. When first diagnosed, doctors had given him less than a year to live. Yet when he came to us, he was in his sixth year—still defying the odds. While he was able to enjoy more time with his family during these gifted years, he also endured more than most: the quiet passing of his wife, the dimming of sight in one eye, and the slow betrayal of a once-strong body—the same one that had stood, steady and proud, on countless riverbanks, casting lines beside his boy. Yet through it all, Peter remained fiercely independent—determined to live, and eventually die, on his own terms. Most of us wondered how he had managed to hold on so long, through such battles, but Peter was sure there was something more for him.

We tended to his basic needs at first, waiting quietly, expecting little. But as the days passed and fall deepened, the air turning cooler outside our windows, Peter seemed to gather strength along with the season. Soon, his voice grew lighter, his appetite returned, and his one special request—Diet Pepsi on ice—became a daily ritual.

Even from his bed, his presence still filled the room. A former Air Force officer and instructor, his frame carried quiet authority. We introduced him to the other gentlemen, and before long, his room became a favorite gathering spot. They swapped stories of hunting and fishing, shared memories of service, and laughed over old times. With Andrew beside him, the bond of father and son was plain to see.

Peter never asked for much, but he welcomed the company. We carried coffee hours into his room, complete with cookies—which he enjoyed with such delight that we suspected they meant as much to him as the conversations. Day by day, he taught us the beauty of savoring small gifts.

As December came and we realized Peter would most likely not see another holiday season, we began to look for ways to include him in the festivities. One particular evening, a storm was blowing hard across town. Snow fell thick and heavy, and for a time, we weren’t sure if our visitors would make it. But slowly, car after car pulled in, headlights glowing through the snow, doors flying open as laughing, joyful teenagers poured into our building, brushing snow from their coats.

They were a large local youth group of thirty—too many for one area—so we divided them into six smaller groups. Each rotated through different areas of the building where residents were eagerly waiting—some sang carols, some shared holiday messages, and others told stories about their favorite ornaments. Peter’s room was one of the stops, and I had gathered the men of the building there, along with Peter and his son Andrew.

Before bringing each group to Peter, I paused with them in the hallway. With his permission, I explained what they would see: Peter’s illness showed—he was thin and frail—but he was also very much alive and eager for their company. I told them this would most likely be his last holiday season, and that their presence here, on a cold December night, was a gift beyond measure.

One of the groups was a circle of boys around fourteen or fifteen. Each had brought along a favorite ornament, their faces lighting up as they told the stories behind them. One boy, about fourteen, carried a homemade gingerbread ornament he had made years before. He laughed as he told how every Christmas he had to fight his brothers to keep them from eating it, his voice animated as he relived the battles and the triumph of seeing it hung on the tree each year.

As I watched each group enter and then leave Peter’s room, I was overwhelmed and moved at the understanding on their faces of the significance of those moments. What began as a simple holiday visit was transforming into something sacred, a memory none of us would ever forget.

A night of routine activity was becoming magical.

As the last rotation wrapped up, we gathered everyone, residents and youth, into the front room. All of the residents were sitting in a large circle with the youth surrounding them. As we thanked them all for the stories and treats, we decided to sing a few Christmas carols before they left. The beauty of their voices—young and old, all singing together—filled the room with holiday joy and spirit; overwhelming and touching.

As we were singing, I felt a tug at my shirt. I turned to see the young boy with the gingerbread ornament motioning for me to join him in the dining room. With tears on his face, he asked if it would be okay for him to give his ornament to Peter. The ornament he had fought for years to protect, he now wanted—no, needed—to give to Peter.

I stood watching as he placed the ornament in Peter’s hands, and saw the smile on Peter’s face as he realized how deeply the boy’s heart had been touched in giving him this gift. I was reminded how powerful a simple gesture can be.

Peter hadn’t defied the odds and stayed longer for himself, or because he feared letting go. He had lived a full and good life and was at peace with where he was going. There was simply one more purpose to fulfill.

Peter was here for the boy. To leave a mark that would outlast his own days. To show him, in a way words never could, that a single moment of kindness can echo for a lifetime.

I have no doubt in my heart that this young boy was changed that night—and someday will touch someone else’s heart with the story of Peter and the Boy.

Written by Lynda Huddleston.

Thank you, Lynda, for letting me share.

Lynda is a certified End of Life doula and chaplain for Primrose Homecare and Hospice. The picture is of her and the original gingerbread boy.

Back in 2012, I read an article by Kerry Patterson of the

Back in 2012, I read an article by Kerry Patterson of the